Do You Really Need Snapchat+?

By Samyukta Pai

There’s a common misconception that economics is just an extension of math, all about crunching numbers. In reality, it’s about how people and businesses respond to those numbers when they change. One of the clearest examples of this is Price Elasticity of Demand (PED) — a measure of how sensitive consumers are to changes in the price of a good or service.

Take Snapchat, for example. Imagine it suddenly raises the price of Snapchat+ from $3.99 per month to $15.99. Most people would see that as a ridiculous jump, not worth the extra money. Because of this poor decision, Snapchat could lose over 100,000 subscribers. That’s PED in action–consumers showing they’re highly sensitive to a price change.

But here’s the big question: would consumers be just as sensitive if the product or service were something they needed in their daily lives? Let’s find out.

So what is PED?

More formally, PED is defined as:

“...the percentage change in quantity demanded divided by the percentage change in price. It tells us how much demand will expand or contract when prices rise or fall”.

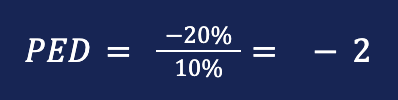

For example, if the price of Snapchat+ subscriptions increases by 10% and sales drop by 20%, the PED is:

The negative sign reflects the law of demand, but economists usually take the absolute value (you drop the negative sign). Here, PED is equal to 2, meaning demand is elastic: consumers are highly responsive.

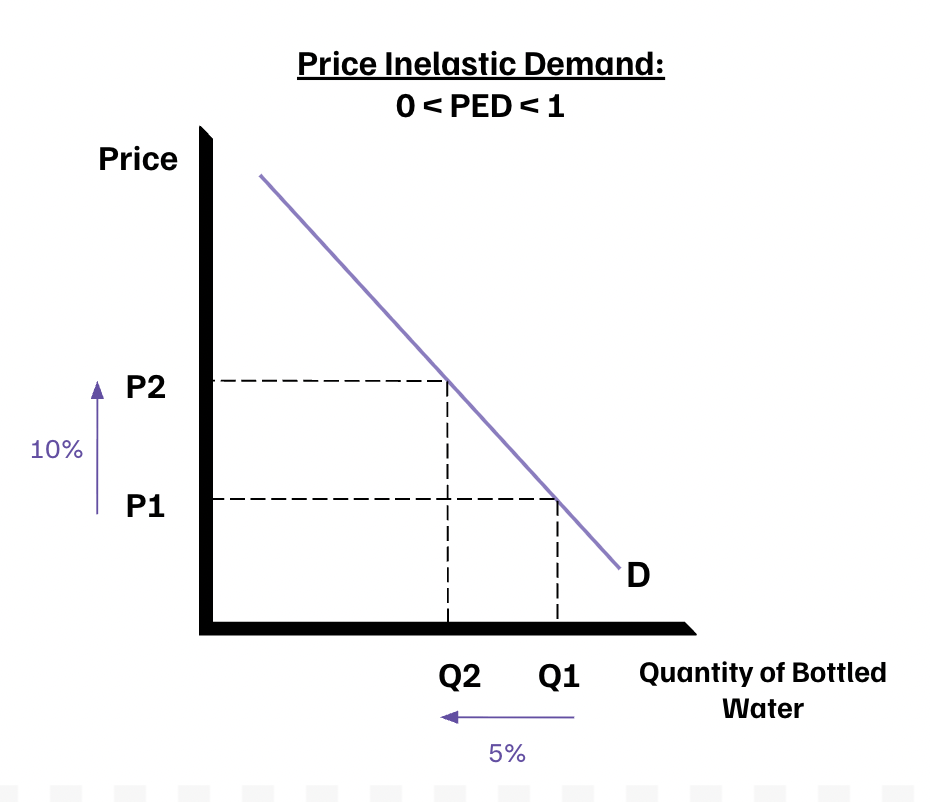

Think bottled water. If the price goes from $1.00 to $1.50, people still buy nearly the same amount because water is a basic necessity. The change in price hardly changes the quantity demanded. Therefore, inelastic demand refers to quantity demanded being relatively unresponsive to price

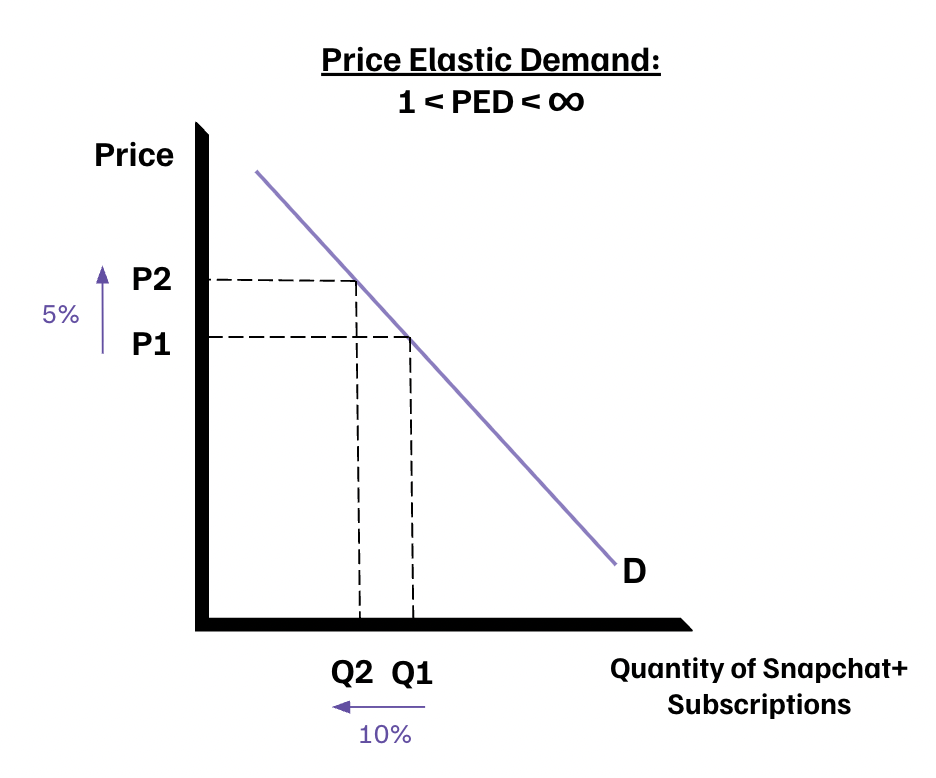

If Snapchat raises its subscription from $3.99 to $15.99, tons of people unsubscribe because Snapchat+ is simply a luxury, not a necessity. The percentage drop in subscribers is larger than the percentage increase in price. Therefore, the quantity demanded is relatively responsive to price.

Imagine a movie theater raises ticket prices by 10%. As a result, 10% fewer people attend. The extra money per ticket is exactly canceled out by the loss in audience size, so the theater’s total revenue stays the same. Therefore, unit elastic demand is when percentage change in demand equals percentage change in price.

For something like insulin, no matter the price increase–from $50 to $500–patients still need it to survive, so demand doesn’t change at all. This doesn’t only go for insulin, but any other life saving medication. Thus, perfectly inelastic demand is completely unresponsive to price.

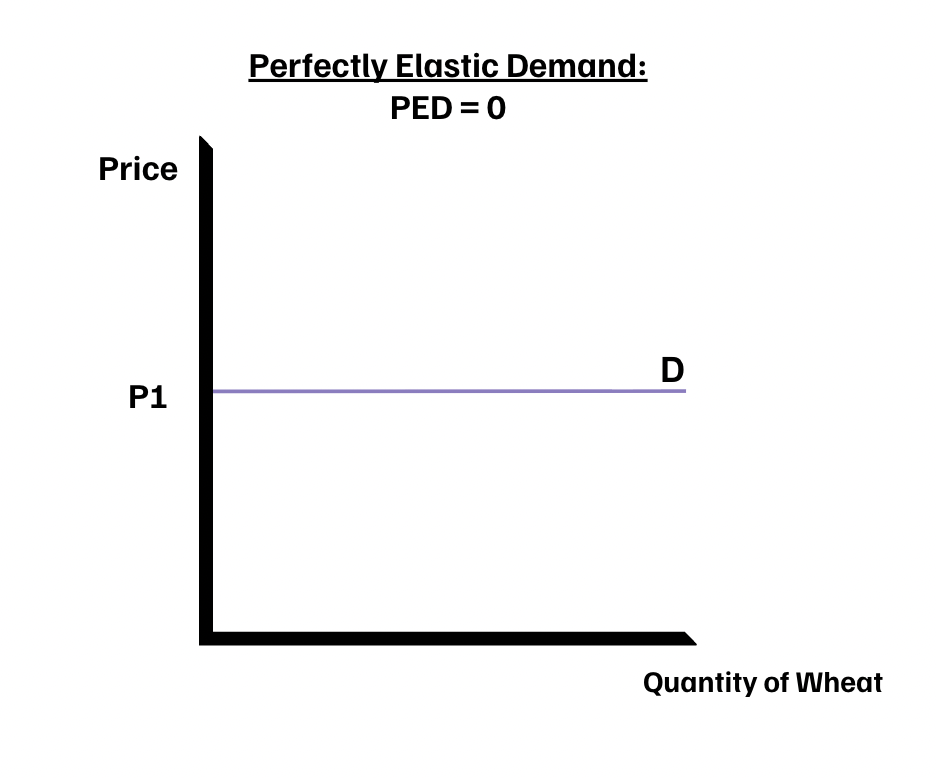

Imagine a farmer selling wheat in a big market. The market price is exactly $2 per kilo. If the farmer charges even $2.01, it is likely that consumers will switch to another seller because dozens of other sellers are offering the same wheat at $2. Why pay the extra money?

The second they go above the going rate, demand drops to zero. Thus, perfectly inelastic is when buyers are infinitely responsive to price. Sellers must accept the market price–any higher and demand vanishes.

Determinants of PED

Do you see a potential pattern in what demands for goods or services are particularly sensitive to price changes? You may have noticed that it is whether the good is a need or a want, a necessity or a luxury. More formally:

Number and closeness of substitutes → More substitutes make demand more elastic (Coca-Cola vs. Pepsi).

Necessities vs. luxuries → Necessities like rice are inelastic, while luxuries like designer handbags are elastic.

Length of time – In the short run, demand is often inelastic (e.g., heating oil), but in the long run, people can adapt, making demand more elastic.

Proportion of income spent – Goods that take up a large share of income (cars, housing) tend to be more elastic.

Addiction and habit-forming goods – Demand for cigarettes or alcohol is relatively inelastic despite price increases.

Maximising Profits

An application of PED is its effect on total revenue (TR) – the total income a company earns from its sales of goods and services. It is calculated by:

TR=PQ , where P is the price of a good/service, and Q is the quantity of that good or service.

If demand is elastic, a price increase reduces TR (consumers cut back a lot), while a price decrease increases TR.

If demand is inelastic, a price increase raises TR (consumers cannot cut back much), while a price decrease lowers TR.

If demand is unit elastic, TR stays constant regardless of price changes.

This relationship is core to understanding how businesses decide whether to raise or lower prices.

Now, it's clear that PED is a tool to better understand human behavior. PED helps explain why people cut back on Snapchat+ when prices increase but still buy water even when it gets a little more expensive. For businesses, PED is a decision-making tool to show whether raising or lowering prices will bring in more money and how customers are likely to react. For governments, it helps predict the effects of taxes, subsidies, or policies on different markets.

This core microeconomic concept reminds us that economics is about the people, their needs, their wants, and the trade-offs they face every day.